Pyzówka 2010

Face Bóg

Facebook is truly becoming ubiquitous, to the point that it can be used in Polish religious advertising.

Below was a poster at the entrance to one of the many churches in Krakow.

“Bóg” (“God”) is pronounced much like the English “book,” but with an obvious “g” instead of “k.”

“Dodaj boga do twoich znajomych” literally means “Add God to your acquaintances,” but a more Fackbook-eque translation would obviously be, “Add as friend.”

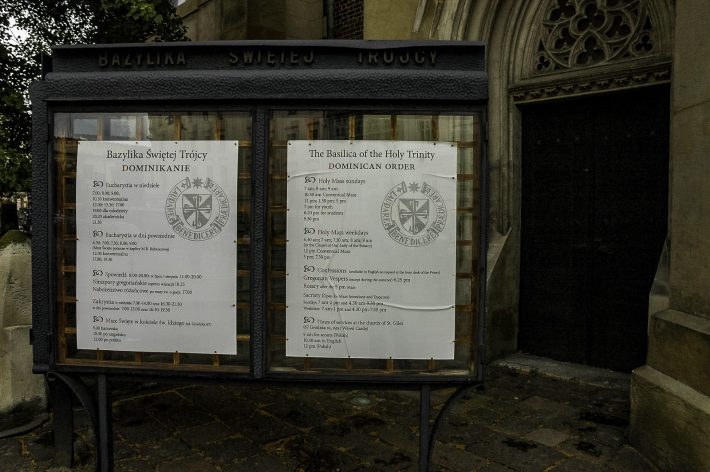

Basilica of the Holy Trinity (Krakow V)

“You know what I’m looking forward to?” I asked K before we left for Poland. “The smell of an old church.”

“Oh, me too,” she replied.

It’s an odor of slightly metallic dampness, old incense, leather, wool, and a thousand other notes that probably only a sommelier or blender of fine pipe tobaccos could notice and describe but which merge for us mere mortals into “old church.” It is to be in the midst of history: the structure is older than America. It is to be in the midst of profound calm: even in the most tourist-filled church, there is reverent silence.

A day in Krakow, responsible only for myself. I decide there is only one thing to do: go into churches. I begin with one of K’s favorites: the thirteenth-century Gothic Basilica of the Holy Trinity.

With so many churches in the Old Town of Krakow, it’s surprising how many masses the Basilica has. There are more on a weekday than on a Sunday at an average Catholic church here in the Old South, a clear illustration of the difference in relative demand. Then again, this particular church is popular among university students in Krakow.

So many of the churches in Krakow — they begin to blend together after a while. That’s the tourist view, I’m sure. To parishioners, there’s a history and a relationship.

Yet, there are little details in each church, little architectural touches that set each one apart. The basilica, for example, has a small upper chapel.

The view provides a little different perspective. Instead of looking up — a common action in gothic churches, and very much by design — one has the opportunity to look down. Somewhat blasphemous in a certain sense: we mortals are to be looking up to God, and here I am looking down. And on what?

A young monk explaining an upcoming ceremony to four young men. I can’t hear what they’re saying, and every picture I take turns out later to be completely, irredeemable blurry. I make a logical assumption: these young lads are about to become monks themselves, but I’m not certain. I can’t eavesdrop without making it obvious, and something prevents me from simply walking up to them and asking. What’s stopping me?

The conspicuousness I always feel as a tourist certainly has something to do with it. Walking around, snapping pictures, changing lenses, taking more photos, changing lenses again — I’m simply a cacophony.

What’s worse, unlike the Catholic tourists, I don’t genuflect as I pass the altar, and I don’t cross myself on entering. I surely stand out, but what’s the problem? We all stand out.

Is it false modesty or simply an overactive ego?

Ну, погоди

Every time L meets Babcia (here or in Poland), Babcia turns L onto a new cartoon. This visit it was Wilk i Zajac (Wolf and Hare). In the classic tradition of the Roadrunner, Tweety Bird, and Tom and Jerry (to name but a few), it is the continuing attempt by a mildly evil character to capture (and presumably consume) an innocent character.

It’s not a Polish cartoon, though. It’s from the Soviet Union, with the first being created in 1969. The Russian title was “Ну, погоди¸” (pronounced “Nu, pogodi” Ну, погоди” is translated “Just you wait!”). It’s easily translated to other languages (I’m sure Poland wasn’t the only Soviet bloc country to have this imported) because about the only words spoken in each episode are “Ну, погоди¸”. The Polish versions translate that as “I’ll show you!”

L watched the DVD so many times that she basically had them memorized. She wasn’t the only one in the house who came to have the cartoons seared into memory. By the end of our stay, I could tell which cartoon was playing just by walking by the living room.

Busted

Up (Krakow IV)

Krakow, like all European cities, is a mix of the old and the new. Young people walk along ancient cobblestone street checking email and updating their Facebook status on their cell phones. McDonald’s sits on an ancient street in a building that is at least twice as old as the chain itself.

Often both are present at the same moment, in the same building. Visiting such an old city is a reminder that often, what’s at street level is the least interesting sight. Or, perhaps more accurately, that which is above is at least as interesting as that which is at eye level.

As I strolled along, taking a meandering walk from the rynek to Kazimierz, the old Jewish quarter, I began to pay attention to the balconies.

In an urban setting, balconies are often the only part of one’s property that has anything at all to do with the out of doors. Parks, beautiful as they are, are after all public property. A balcony is the only “yard” a city dweller might own.

A few flowers and it’s positively garden-like.

Storage is another balcony option. I had a good friend in Warsaw who had a “balcony” at his apartment that couldn’t have been more than ten square feet: just a little spot to stand. He stored his bike and a couple of other items on the balcony. After all, what else could you do with ten square feet? As a non-smoker and non-coffee drinker, he couldn’t even enjoy a morning cigarette (if such things could be enjoyable) and cup of coffee on his balcony.

As in most urban areas, space is at a premium. Some decide to turn their little bit of outdoors into an additional room. Then neighbors get balcony envy and enclose theirs,

resulting in an alleyway of enclosed balconies.

Given the size of some apartments I’ve visited, it makes perfect sense.

Still others, with a more classic balcony, simply leave it alone. Then again, if one’s balcony is the size of others’ apartments (and I have been in apartments in Warsaw that tiny), one probably has enough apartment on the other side of the balcony to make such a conversion unnecessary.

Yet not everyone has a balcony, especially in the Old Town. This is not to say they haven’t carved out their own little outdoor garden. Some, more extravagantly than others.

It makes for a bit of color in an otherwise gray setting.

Many, however, just leave well enough alone. Perhaps they figure it’s not worth the time. Perhaps the reason that there’s not much use, given the state of the pre-war facade.

With all the renovation going on all over the city (thanks, European Union), it’s only a matter of time before such sights disappear. In a way, that’s sad: such decrepit facades bear witness to history. They show the gritty underside of Poland, and they serve as a reminder to visitors that, as with much of Europe, the city hasn’t always been filled with days of Italian ice cream and walks in the parks.

It also shows one of the paradoxes of modern Poland. The building above is literally on the rynek: the most prized location in Krakow real estate. Yet the roof is literally pathetic. It’s the same as in Furmanowa, the meadow overlooking the Tatra Mountains in Zab: prized real estate that’s used for cultivation.

And yet the irony: so many Poles lament how so many of their compatriots have turned so materialistic in the last few years.

Top Floor

K’s parents have a large house. They have to: they run a little noclegi business — something like a bed and breakfast, but more often than not, without the latter.

This is the view from their highest balcony.

All the quirks of Poland, on display. The relatively rich live beside the poor. They both live next to an enormous flea market, where everything is available, and all prices are negotiable. All framed by the mountains that give the region its beauty and its culture.

In Motion

During K’s next-to-last night in Poland, we went out for a little family-and-friends party. I posted several pictures, but only now have I gotten around to the video.

Who could listen to this and sit still? Apparently, not many…

Girls Singing

The Girl loves to sing. It turns out her cousin does too, as does the daughter of her godmother.

Two Polish songs and a number in English about butterflies.

Readjusting

Coming back to the States after a few weeks in Poland requires a few adjustments. Among them:

Driving a car with an automatic transmission. My left foot is bored, restlessly searching for a non-existent clutch, and my right hand wanders to the gear shift every time we approach an intersection.

Driving a car with an automatic transmission. My left foot is bored, restlessly searching for a non-existent clutch, and my right hand wanders to the gear shift every time we approach an intersection.- Hearing English everywhere. This always surprises me: I get used to having to do a little, occasional mental work to understand what’s going on around me. Hearing rivers of voices that are all intelligible to me initially feels a little intrusive.

- Hearing other languages everywhere. I go to the grocery store, and I hear Spanish, German, Hindi, and Arabic.

- Seeing different races. In the passport check line at the airport, I saw all the colors that make America. In Poland, I see a non-white walking down the street, and it’s difficult not to stare.

Seeing boys’ underwear in public. On the way back home, we stopped to grab a little something for the Girl to eat because she didn’t eat too much during the journey. Waiting in the check-out line: two adolescent African American boys with their pants seemingly at their knees. I’d mentioned this style in Poland: it seemed incomprehensible to them. It seems incomprehensible to me.

Seeing boys’ underwear in public. On the way back home, we stopped to grab a little something for the Girl to eat because she didn’t eat too much during the journey. Waiting in the check-out line: two adolescent African American boys with their pants seemingly at their knees. I’d mentioned this style in Poland: it seemed incomprehensible to them. It seems incomprehensible to me.- An entire row of paper towels in the supermarket. American consumerism is all about choice. What could possibly be the difference among the towels?

Having someone bag your groceries for you. Perhaps it’s the ultimate sign that Americans are in some way spoiled, but it still surprises me when I go into any grocery store in Poland and have to frantically bag my own groceries before the next customer’s purchases start sliding down into the bagging area. Why not bag as the cashier working? That’s another thing to get used to:

Having someone bag your groceries for you. Perhaps it’s the ultimate sign that Americans are in some way spoiled, but it still surprises me when I go into any grocery store in Poland and have to frantically bag my own groceries before the next customer’s purchases start sliding down into the bagging area. Why not bag as the cashier working? That’s another thing to get used to:- Not having to pay for the bags used in the process. No one provides free shopping bags. The cost is nominal, but the cashier always rings the bags up last. It doesn’t make sense.

- Not having potatoes with every meal. I don’t want to see a potato, in any form, for at least a month.

- Being warm. In the early morning, temperatures in Jablonka could be in the high forties. During the first week, the temperature seldom rose to the mid-sixties. The warmest it ever got was seventy-five. Back in South Carolina, it’s almost seventy-five when we wake up. It takes some getting used to.

Irony?

Bags Packed

Henry John Deutschendorf, Jr. made the sentiment famous: bags are packed, and L and I are ready to go, next post from the States, yet mixed emotions linger.

“I want to go home” became L’s refrain a couple of days back, and talking to K on Skype only worsened the situation once. There were variations: “When are we going home?” “Are we going home tomorrow?”

I, too, am ready to go: vacation is great, but returning home is the true heart of any journey. K awaits, as do infected trees await, a likely overgrown lawn, a course to begin Monday, and a host of other things. One can only sit around doing little for a very short time before the feeling of uselessness sets in.

And yet, leaving Poland is always bittersweet. “Would you want to move back?” friends and family asked. Or “When are you all moving back?” Would we move back? Yes, and no. When are we moving back? Soon and never.

I wonder if other countries produce such mixed emotions among its ex-pats and virtual ex-pats?

Cleaning

Dolina Kościeliska

“Bolą mnie nogi,” was L’s chorus. Aching legs was something to expect: after all, taking a little, semi-city girl for a walk in the mountains is no walk in the park, if one will excuse the obvious pun/cliche. Especially when she’s the kind of girl that wants to climb every obstacle she encounters.

A beautiful morning with no other plans, though, called for an introduction to the Tatra Mountains.

We set out with two rolls, a container of strawberries, and a bottle of apple juice. And a plan: walk as far as we can up Dolina Kościeliska (Kościeliska Valley). With a prognosis of rain only a couple of hours away, I wasn’t terribly optimistic, but even a twenty-minute walk would have been worth it.

The two rolls lasted only a few minutes.

“Can I something to eat?” the Girl asked shortly after we started walking. Immediately after finishing the first roll — obviously not even pausing for pictures — she asked for a second. The strawberries lasted through the first two breaks.

Surprisingly, and proudly, the complaining about the legs didn’t happen until we’d almost reached the point at which we actually turned around: a small chapel situated between two large pines. Up to that point, it was all fun and smiles. Horse-drawn carts traveled up and down the road, and the Girl only expressed regret that we weren’t travelling in more style.

It seems to me that a three-and-a-half-year-old stomping her way up a small incline toward an unknown reward is style enough. Still, the Polish idea of recreation is different from the American idea, and the Girl wasn’t the only, or even the youngest, child heading up the valley. In fact, it was from another three-foot sojourner that the Girl got the idea of aching legs.

“Bolą mnie nogi,” a young girl said as she passed us with her father. Shortly thereafter, L declared, “Bolą mnie nogi.” Coincidence? Definitely. At the same time, certainly true, considering how far she’d already walked.

We took a break at a small chapel, and while L polished off the strawberries, I snapped a few pictures and glanced at the sky. The wall of gray that characterized the Polish sky during most of my years in the country was bearing down on us. Literally a wall: sunny, blue sky on one side, solid gray sky on the other. Behind, the sky was an ominous dark gray that strongly hinted at rain. It was two hours later than forecasted, and for that I was thankful.

And so was the Girl.

“You want to head back now?” I asked rhetorically.

“Do babci?”

“Yes.”

She slammed down the lid to the container and declared, “Tak!”

Krakow III

I first made the journey to Krakow in the summer of 1996. I took an 8:00 am train from Radom, an industrial city just outside of Warsaw, to Krakow along with a compartmentful of co-volunteers from the Peace Corps. An industrious group took a train leaving at five something in the morning, but valuing my sleep more than sightseeing, I waited for the next train.

In ’96, Krakow Główny was an average Polish train station. There was a parking area in front, and across the street from it was the main bus station: a sad, dirty affair that I came to avoid at all costs. Krakow Główny wasn’t much better, particularly the waiting area.

These days, it’s somewhat more spectacular.

The approach to the market square is much the same as it was fourteen years ago.

Out of the station, a broad walk leads to a passage under Westerplatter Street.

In the mid-ninties, this was where the “shopping” started. The intended clientele here was not the few Westerners who might, in comparison, be relatively rich. These small shops and kiosks sold things for Poles; by and large, they still do.

Emerging from under Westerplatter Street,

the walkway passes beside the Juliusz Slowacki theater.

The walk to the rynek continues down ulica Pijarska past the only real tobacconist I could find in Krakow.

It was here that I first bought what became my favorite pipe tobacco: Dunhill’s Mixture 965. Dunhill no longer produces the blend, and even if they did, I wouldn’t be able to buy it here now: no real tobacco blends to speak of.

The walk continues by the Florianska Gate,

turning left onto Florianska street.

The MacDonald’s on Florianska has been there since my very first visit. Whenever I was in Krakow, I dropped by. Not for food, but for the one thing that American chains did better than just about anyone else in Poland at that time: bathrooms. Only at McDonald’s could I count on clean facilities, and apparently others discovered that as well: within a year, McD’s had switched to a pay bathroom, something seemingly unthinkable for many Westerners but common at that time (and still quite common). One had to be a customer to use the restroom, so I bought a small order of fries.

My first visit, I was completely unaware what awaited me at the end of the street.

Stepping onto the rynek (main market square), it’s difficult not to stand motionless in awe. But that’s for another day.

A New Photographer in the Family

L’s been sick. As she recovers, we decide to go out for a walk.

Her photographic soul comes alive:

It’s good to see a building interest in something I love. It’s bad for Babcia: she ends up carrying everything L left the house with.

Somehow, I didn’t manage to get the actual pictures she took uploaded. Next time…

Party! (Again?)

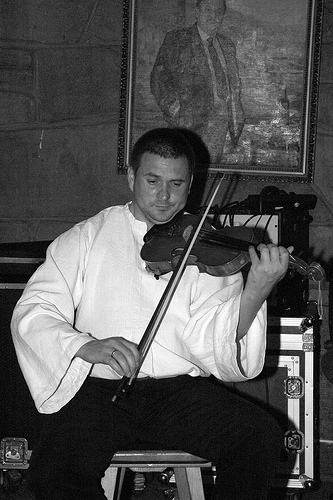

K’s last full evening in Jablonka — what else to do but go for a little party? This one is a little different. For one, we’re going out, not staying in: less clean up. Second, we have live entertainment, an amazing string band (video coming later). Third, it’s a smaller group: more intimate. Finally, I’ve agreed not to be such a prude and drink a little. Which means, with live music, that I might be induced into dancing. Or I might shock everyone and initiate it.

It’s rare that I’m among the first in the room that makes it to the dance floor. It’s even rarer when I initiate it. There are obvious exceptions. Fortunately, I know the required components, and I can stay well away from them if I don’t feel like making a fool of myself.

One component, which is honestly optional, is a little bit of alcohol. It lowers inhibitions, and that warm feeling after one or two shots of vodka makes my toes twitch. Metaphorically speaking, of course.

Another component is having someone I really wish to dance with. K loves dancing, as does L, and they will dance with just about anyone, including solo dances. I take a more circumspect view of dancing. If I’ll be getting up in front of other people and wiggling my body in this or that odd, unnatural way, and perhaps enjoying it, it will have to be with someone who, at the very least, I like. Better yet, someone I love.

All that is to say I don’t love dancing.

K does.

K will dance with anyone. She’ll dance alone in our living room, tauntingly.

“You know you love this song,” she says with her bright eyes. “Why not dance?” I can give myriad excuses.

When she gets with someone else who’s equally crazy about dancing, the results are predictable and lovely:

Everyone is in a dancing mood. The only person who doesn’t get the dance he wants is Dziadek. He keeps asking L for a turn around the floor — and it would have literally been a turn for L — but she keeps denying him. Maybe she’s honing her skills; perhaps she’s just being a typical three-and-a-half-year-old.

At the heart of all the movement, and the number one component to getting me on the dance floor, is the live band. All trained in traditional styles, they have a flair for original touches of jazz, Gypsy, Jewish, and Eastern modes in their music. The result makes it difficult to sit still.

After filming several of their numbers (to be posted later, after I regain access to editing software), I take the bottle up to their table and pour a round or two for them.

“You guys are going to be on the Internet in a couple of weeks,” I laugh.

“On YouTube?” one asks.

“Of course.”

“What will be the title?” a second inquires.

“Really Good Music,” I tell him, but that is, as my father would say, a little tightened up from the original.

Once, Upon A Time

I first arrived in Poland in June 1996. I stayed until June 1998, when I went home for the summer before returning for a third year. In 2000, I went back to Poland for a week. In 2001, I moved back to Poland to teach English, returning to the States for the summer of 2002. K and I left for American in 2005 and made our first return visit in 2008. Now it’s 2010, and I’m back in Poland for the fourth, maybe fifth time. Each time I arrive, one of the highlights has always been the unexpected encounter with former students.

Even when I lived here, I would bump into kids I hadn’t seen in a couple of years (by then, adults), and we would chat a bit. It’s great to see what your efforts have led to. Not all of them use English on a regular basis, but some do. Several of my students became English teachers (four that I can think of). A couple of them used English to communicate with the individual who would eventually become his/her spouse. Several of them worked abroad and used English with their employers.

During our return of 2008, I met at least ten former students. I bumped into four or five at a folk festival. One or two worked in shops that I visited. One married the son of a neighbor of my in-law’s. I met a few at the Wednesday market in Jablonka. Each time, it was the same conversation: what they’re doing; what I’m doing; plans for the future. Maybe a word or two about this or that amusing incident that happened in class years ago.

This year, I’ve met one, and only in passing, literally: he was in a car, I was on foot with the family. And that stands to reason: the kids I taught during my first three years are now in their late-twenties or early thirties. They have families of their own, and most likely they have achieved their wish of moving out of the village. I’ve heard as much about a few. The kids that I taught during my second stint in Poland are now in their early- to mid-twenties. They’re done with college, possibly married, with new worries and new passions.

I walk down the street now and see young, new faces. I search the features for a similarity — perhaps he or she is a younger sibling of this or that student. Very unlikely, I realize, but I only recently realized why it’s so unlikely. The kids who are now in high school, whom I would now be teaching, were only newborns when I first arrived. At most, they were two or three years old.

It’s a different world.

K has noted the same thing. “I go into the shops,” she told a friend, “And every single face behind the counter is new.” The teenagers have grown up, moved on, and miraculously, others have filled their spots.

It’s really the curse of being a teacher: I stand still in time. I remain with one of the twelve milestones of one’s life, and I get older while the kids get relatively younger.

It’s also the surprise of the passing of time. Once, we all thought we were ageless, possessors of infinite youth and endless energy. As adults, we go back to a spot where we felt that invincibility, and though we shouldn’t be, we’re surprised that nothing is the same, either with ourselves or with the environment itself.

Naturally, in noting all of this, I’m saying nothing new. Heraclitus discussed it 2,500 years ago, using his famous “never see the same river twice” metaphor to illustrate the centrality of change in the universe. Perhaps part of the nature of change is its sensitiveness. We don’t even realize it’s happened until we return to one of the poles of our lives that serve to solidify and give meaning to our lives, and then we see how much the world — including us — has grown.

Afternoon Walk

I always feel a little guilty, heading out with a camera and my backpack of accessories to take a walk in Jablonka and photograph people who are putting in a normal day’s work in the field that is harder than I do most days of my life. That is why I always hesitate to approach. A massive zoom lens — call it the coward’s approach.

fortunately, hard-working Poles are not the only attraction. Much of the farm work here — such as turning hay on the fields for drying — is done with somewhat antiquated machinery by commercial/industrial Western farm standards. The machines are rusty but elegant reminders that not all heavy machinery needs computer chips and miles of cables. A few rusty springs will do just fine.

At first, one might say, “There is no comparison to the scale of large, commercial Western farms,” and that’s correct, partially. But when you see how Orawians load a trailer with hay, it puts questions of scale into proportion.

Remember: this trailer was load manually: one or two guys on the ground tossing up pitchfork-loads of hay to one or two guys (or women, or even adolescents) standing on the growing pile. At least that’s how it ends. The wagon actually has a device that forks the hay into the wagon bed automatically, but one doesn’t make wagon loads this high by letting machines do all the work.

The odd thing about the fields they’re working is their shape: long and narrow. Most of them are no wider than thirty or forty feet, but they are often three or four times that long.

It’s the result of generations of inheritance: dividing the land to pass it on to further generations creates not a checkerboard but, well, yes a checkerboard, but out of some Dali painting, where the dimensions and shapes of everything are exaggerated and warped.

The big mystery: with so many fields crammed side by side, how does anyone know anyone’s borders? I go out for a walk and find one field’s hay cut, neatly put into piles; the neighboring field is wild with grass and flowers. How does the owner know where his land stops and his neighbor’s begins?

“They just know,” I’m told.

Apparently, though, some have gone to the cost of having surveyors come out and set boundaries.

Others use less technologically-dependent methods.